- EAN13

- 9782855396576

- Éditeur

- EFEO – École française d'Extrême-Orient

- Date de publication

- 3 novembre 2008

- Collection

- Études thématiques

- Nombre de pages

- 240

- Dimensions

- 28 x 18,5 x 1,4 cm

- Poids

- 750 g

- Langue

- fre

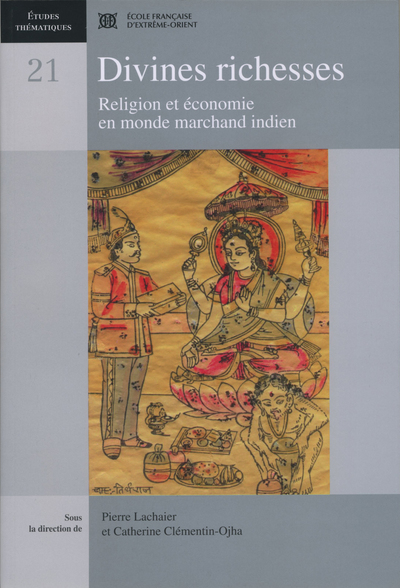

Divines Richesses, Religion Et Économie En Monde Indien, Religion Et Économie En Monde Marchand Indien

Pierre Lachaier, Catherine Clémentin-Ojha

EFEO – École française d'Extrême-Orient

Prix public : 45,00 €

Divines Richesses, religion et économie en Monde indien.La plupart des études sur les marchands et industriels indiens tentent à négliger leurs pratiques religieuses bien que celles-ci soient communément associées à leurs activités. Comment idées et comportements religieux s’interpénètrent-ils dans les pratiques professionnelles concernées ? Les textes rassemblés dans ce volume proposent des éléments de réponse. Écrits par des indologues, des anthropologues et des spécialistes des sciences religieuses, ils examinent les formes traditionnelles de valorisation religieuse de la richesse ainsi que la manière dont les acteurs marchands de différentes croyances – hindoue, jaïne, musulmane, chrétienne – les perpétuent aujourd’hui dans le cadre de l’économie indienne moderne. Ils s’efforcent aussi de comprendre pourquoi les marchands sont souvent membres de groupements sectaires volontaristes, et si cela résulte d’une affinité entre leurs activités et un ethos religieux particulier ou du bénéfice que leurs affaires tirent de telles affiliations. Ils traitent également des différentes formes de dons, les distinguant selon la façon dont on les suscite, les modalités de leurs collecte, de leur remise ou de leur affectation, ou encore selon la qualité des donateurs et donataires. En adoptant ces points de vue, ce recueil d’articles rappelle qu’en Inde les sphères politico-économiques, sociale ou religieuse ne sont pas nettement délimitées ou circonscrites.Divine Riches, Religion and Economics in the Indian Merchant World.A majority of studies on Indian merchants and industrialists tend to neglect their religious practices even though they are commonly associated with their activities. How do religious and economical ideas and behaviours interpenetrate in their daily activities? The papers collected in this volume deal precisely with this question. Written by indologists, anthropologists and specialists of religious sciences, they examine the ways in wich the usual forms of wealth have been religiously valorized, how mercantile actor of various creeds – Hindu, Jain, Muslim, Christian – perpetuate them today within the frame of the modern Indian economy. They also try to understand why the merchants often belong to voluntary sectarian groupings and whether this is due to some sort of affinity between such religious affiliations and their activities or because their economic activities benefit from them. Contributions deal with different forms of gifts, distinguishing them according to the way they are solicited, collected, delivered or allocated, or to the qualities of the donators and donees. From these various points of view, the essays collected in this volume are a clear reminder that in India, the political, social and religious spheres are not clearly delimited or circumscribed.